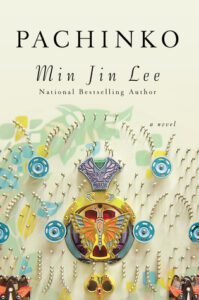

Pachinko by Min Jin Lee is a novel of beauty and perseverance, which shows an unflinching view of Japan’s treatment of Koreans, both during the occupation of Korea and after World War II. The novel follows one family through four generations, starting in 1910 and finishing in 1989. If you could go back in time and observe the life of your great-grandparents, could you see the outline of possibilities that shaped you? There are moments in Pachinko that affect characters decades later. An infatuation, a mistake, a desire for a better life and what does that do to a child or grandchild? Are there currents one’s family create, which are impossible to escape? One question in the novel revolves around fate and freewill, as Christianity is central to some of the character’s lives. But, in the face of systemic racism, the question of fate versus freewill is subverted.

Pachinko by Min Jin Lee is a novel of beauty and perseverance, which shows an unflinching view of Japan’s treatment of Koreans, both during the occupation of Korea and after World War II. The novel follows one family through four generations, starting in 1910 and finishing in 1989. If you could go back in time and observe the life of your great-grandparents, could you see the outline of possibilities that shaped you? There are moments in Pachinko that affect characters decades later. An infatuation, a mistake, a desire for a better life and what does that do to a child or grandchild? Are there currents one’s family create, which are impossible to escape? One question in the novel revolves around fate and freewill, as Christianity is central to some of the character’s lives. But, in the face of systemic racism, the question of fate versus freewill is subverted.

Pachinko

As a unifying metaphor, pachinko, works well in the novel. Pachinko is a game of chance, it mixes the skill of the player (though that may be negligible) with the predetermined paths of the pins as fixed by the pachinko parlor. The game is often described as looking like a vertical pinball machine and the player launches a small steel ball up to the top and then uses a knob to guide the ball to winning baskets. While gambling is outlawed in Japan, pachinko functions as a shell-game in which players win prizes and then “sell” those prizes to a store next to the pachinko parlor for money. The game is a also central to the novel, because under Japan’s racist policies, pachinko was an area where Koreans could work, compete, and earn decent money.

Faith

In talking about fate and freewill, faith is a strand that winds its way through the novel. Sunja’s husband, Isak, is a Christian minister who comes to Osaka at his brother’s invitation. The taxes imposed by the Japanese on Korean landowners made life in Korea worse. As a result, leaving Pyongyang to be with his brother and work as a minister in the church seems like a good plan to Isak, even though his life has been marred with illness. Isak marries Sunja in an act of faith; she’s pregnant with a married man’s child. Isak sees the chance to make a sacrifice that will rescue Sunja and repay the debt he feels is owed to Sunja and her mother through their long care of Isak while he was sick. One of his requests is that Sunja love Jesus and worship God.

What does loving Jesus mean when it’s predicated on a path of stability? How can Sunja say, no, to Isak? We see Sunja not believing in God. We see her wanting to talk to the spirit of her father, Hoonie. But, over time we see if not faith, then the presence of God in her life. For her sister-in-law, Kyungee, faith in God guides her throughout life and provides a foil to Sunja’s struggle. Kyungee’s faith is tested as Kyungee’s husband suffers debilitating injuries.

I was reminded of the work Shūsaku Endō, who’s most well-known novel, Silence, focuses on the kakure kirishitan or hidden christians in Japan. In Pachinko, we see the Japanese government crackdown on the Christian faith. People are forced to pray at Shinto temples in public gatherings. It’s at one of these events that turn the novel and change the course of the character’s lives.

Dickensian

One of the characters in the novel studies English literature at Waseda University. There are references to Charles Dickens, but the overall narrative of Pachinko echoes Dickens. First, the novel surfaces socio-economic and class issues. Secondly, the way the brothers Noa and Mozasu strive to carve out a life for themselves is reminiscent of David Copperfield and Pip’s desire to better themselves. Finally, the character of Hansu reminds me of the nefarious elements in Dickens’ work, where one has a character of means and questionable morality meddling in the lives of others.

고생, Suffering

The women in Pachinko often say go-saeng and “a woman’s lot in life is to suffer.” Children die. Work must be done. Men make the rules. It’s life in the patriarchy and women’s roles are to bear children and perform domestic work. Sunja’s mother marries young through an arranged marriage. Sunja, pregnant and alone has a bleak future until Isak comes along. Kyungee must bow to her husband’s demands and forego her desires and dreams. A minor character suffers in a sexless marriage as she finds herself stuck in the role of caregiver. Etsuko loses custody of her children and is ostracized for having an affair. Hana moves from hostess to sex worker as her body seems to be the only part of her valued by society. Suffering cements the women’s stories together. They suffer through their losses and through the opportunities which are denied.

Overall

Pachinko is a wonderful novel. There are a few moments that feel rushed in the final quarter of the book, but overall, I found the book to be beautiful, engaging, and full of emotion. You’ll care about the characters. You’ll celebrate their victories and be crushed by their pain. Most importantly, you’ll discover a story about people that may be new to you. While, I knew a little bit about how Koreans were treated in Japan, I was quite ignorant on the history and depth of that mistreatment. Pachinko teaches the reader as well as entertains.

Pingback: Quitting Haruki Murakami | Scrivler